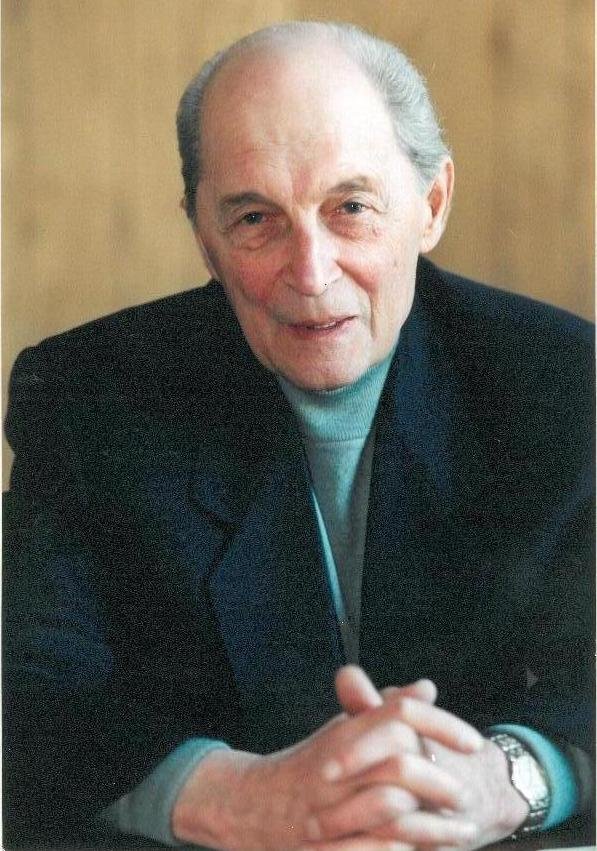

Semyon Ariya, godfather of the Soviet and Russian legal profession, does not enjoy being in the spotlight. This could have something to do with the fact that he just turned 90 in December. But Mr. Ariya has made an exception to speak with RAPSI about perhaps his most famous client, Boris Berezovsky.

Boris Berezovsky, 67, self-exiled Russian businessman and critic of the Kremlin, was found dead in the bathroom of his Surrey home on March 23. Over the last several years, the tycoon’s life was not easy. He frequented London’s High Court of Justice alternately as claimant and respondent in a series of high-profile lawsuits. When Berezovsky suddenly passed away he left behind a tangled web of legal and financial disputes and obligations.

- When did you start working for Boris Berezovsky?

- I became his lawyer in 1999 and remained so almost throughout his London exile (Berezovsky emigrated from Russia in late October 2000 and was granted political asylum in the UK in September 2003 – RAPSI). He treated me with the utmost respect. He needed me for a number of reasons. I was already his English lawyers’ permanent advisor on Russian law, as his innumerable lawsuits abroad were handled by English barristers. And I was also useful because I could hold him back if necessary.

- Do you mean you would warn him against doing something thoughtless or risky?

- Exactly.

- Can you give me an example, without breaking lawyer-client confidentiality?

- What confidentiality can there be now? Except perhaps something that could dishonor him personally. I did know a lot about his private life, and I am still not at liberty to talk about it.

For example, during one of my visits to London I spoke with Yuly Dubov (one of Berezovsky’s closest associates, now a UK resident – RAPSI). And he told me the decision had been made to lodge a claim against Russian law enforcement agencies in the matter of a criminal case opened in Russia against Berezovsky. He wanted to go straight to the European Court of Human Rights. I was strongly opposed to such a dubious move.

- But why? The ECHR at the time did not do the Russian state too many favors.

- It’s quite simple. Should Berezovsky have won the case, he would have been able, in theory, to use the ECHR’s decision in all of his other litigation with the Russian authorities. But Russia also could have just ignored the ECHR’s ruling. After all, Strasbourg’s decisions, until a certain time, were just advisory rather than binding. On the other hand, if Beresovsky had lost the case, the ECHR’s decision would have become a strong argument against him.

Dubov suggested I say this directly to Berezovsky. So I did, and after hearing my reasoning, Berezovky thought about it for a few minutes, then told his aides to cease preparing the claim.

- Were there instances, however, when Berezovsky disregarded advice and warnings?

- Of course there were. I cannot pretend to have been an undisputed authority for him.

- Going back to the early days – the Aeroflot hearings – you had to rest the case at just about the very beginning. Did your client insist on this?

- Berezovsky did not instruct us to stop working on the case altogether. He told us to abstain from attending the hearings. That was his particular form of protest. We had to comply. But we worked with court-appointed lawyers. In fact, we didn’t stop working on the case in 2007, as many media outlets claimed, but just two years ago.

- Concerning another lawsuit, in a London court this time, against Roman Abramovich in 2012: some say that Berezovsky’s defeat was one of the causes of the depression he suffered prior to his death. Was that lawsuit a gamble?

- It was beyond a gamble: it was a totally inexplicable, impulsive action. How could he dare embark on a lawsuit without any evidence whatsoever, relying on purely Russian notions such as “krysha” (an unofficial protection-for-money practice common to the Russian business world of the 1990s – RAPSI). All he had was his conviction that Abramovich’s conscience would wake up in court. Alas, when big business is involved, conscience is fast asleep. It’s such a pity I was not at his side at the time. It was so clear that this was a crazy venture!

When Badri Patarkatsishvili (Georgian billionaire and Berezovsky’s business partner, died in London in 2008 – RAPSI) suddenly died, Berezovsky found himself in the same situation as before the Abramovich lawsuit. They had business together, which Patarkatsishvili handled while Berezovsky was busy playing political games. When his business partner died, Berezovsky’s only hope was that Patarkatsishvili’s widow, who knew everything about their business dealings, would have a pang of conscience. The outcome was the same – nothing. This is just my personal view the situation.

- What will become of Berezovsky’s money and property? He had many children, a few ex-wives, and property both in Russia and in the UK. It’s all tangled up. Has anyone applied to you for help in sorting it out?

- It is unclear at this stage who exactly could request help. His first wife had been taken care of materially back in Russia in the 1990s. Galina Besharova, his second wife, got everything she wanted while she lived in England. And she cannot seek my services, as no legal claims have been filed. Yelena Gorbunova, for all I know, became his enemy (Berezovsky’s former common-law wife who sued him, shortly before his death, for £5 million, proceeds from the sale of property in the UK – RAPSI). My personal impression is that his stressful private life was one of the causes of his suicide.

- Are you inclined to believe this version of Berezovsky’s death?

- Yes, whatever else is being said now, it was most likely a suicide. This is just my personal opinion, though. Let’s wait for the British authorities’ final conclusions.

- When did you last talk to him?

- We spoke on the phone from time to time; the last call was a couple of years ago. But you can’t see facial expressions on the phone, and the voice often conceals emotion. Based on what’s been said by those who were near to him around the time of his death, it’s entirely convincing that it was suicide. For my part, I remember him as a self-disciplined, extremely active man without any signs of depression or lack of energy.

Interviewer: Vladimir Novikov

It is an abridged version of the interview. You may find a full version in Russian here.