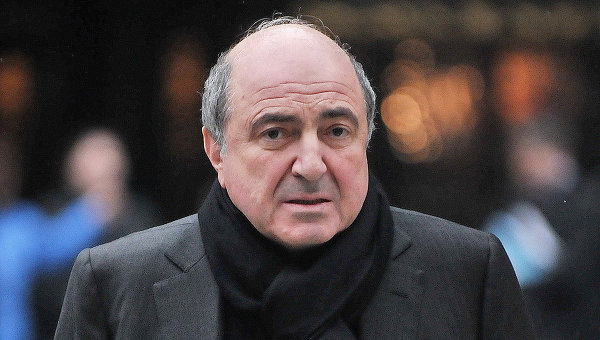

MOSCOW, March 25 – RAPSI, Ingrid Burke. The fate of much of Boris Berezovsky’s estate may pass under Russian law pending a determination that he had maintained Russian domicile during his years in self-imposed exile, according to two experts in UK probate law that spoke with RAPSI Monday.

Speaking with RAPSI, solicitor Tony Millson of Royds solicitors, an expert tax and estate planner for wealthy individuals in the UK and abroad, explained that any real property Berezovsky owned in England at the time of his death – including land, houses, and flats – will pass under English law. However, all personal property comprising the rest of his estate – including cash, art, cars, jewelry, and anything else unattached to British soil – would pass under the law of his domicile.

Thus, the determination of which nation’s laws will apply to Berezovsky’s personal property will likely hang on a domicile analysis.

In overly simplistic terms, the English legal concept of domicile can be seen as a highly complex analysis leading to a determination of one’s home. A person can reside in any number of places, but can only be domiciled in one.

According to Pemberton Greenish partner and probate expert John Goodchild, in its most straight forward equation, domicile is determined on the basis of an individual’s physical presence in a place, paired with his intent to continue residing there indefinitely. He notes, however, that various sub-rules apply for less cut-and-dry calculations.

He explained, for instance, that if a person is born and raised in Russia, but leaves the country at a certain point in favor of residency abroad, Russian domicile would only fall away if that individual takes up foreign residency with the intention of remaining abroad indefinitely.

Berezovsky fled Russia in 2000 and was granted UK asylum in 2003. The fact of this asylum grant in itself, however, would not eradicate his Russian domicile.

According to Goodchild: “Quite often… people will say, ‘I’m in England. I’m spending 365 days a year here. But if cicumstances were different, I would love to return to Russia. But I can’t go back there because of politics…’ [In this case,] they keep the original domicile.”

It has been widely reported that Berezovsky longed to return to Russia.

Dmitry Peskov, Press Secretary for Russian President Vladimir Putin, told Russian television channel Russia 24 that Berezovsky had written a personal letter to Putin shortly before his death imploring the president to permit his return to Russia.

The Economist reported Monday that one day prior to the oligarch’s death, he had made an off-the-record comment to a Forbes journalist that, “To return to Russia. There is nothing I want more than to return to Russia.”

Millson zeroed in on this point as well. When asked about the domicile-determination impact of Berezovsky’s public desire to return to his homeland, he responded: “That militates in favor of his not being domiciled here. From his tax point of view in our country, that would be good news because if he wanted to go back either when he was alive or when he was dead to be buried, that’s very good evidence that he hadn’t put all his eggs in one basket.”

Millson agrees in the end with Goodchild that a determination of Berezovsky’s domicile will prove central to any determination of the fate of his estate.

Millson speculated that if Berezovsky had in fact publicly proclaimed his desire to return to Russia, “I’d be quite confident saying under English law he’d be treated as being domiciled in Russia, and therefore Russian law would apply to his personal property, not English law.”

Millson noted that back when Berezovsky was extraordinarily wealthy, he may have been tempted to retain his Russian domicile for tax purposes, adding that this is a common move among Russian oligarchs residing in England: “If somebody is domiciled [in England], they’re taxed on their worldwide assets when they die. But if they’re not domiciled here, they’re only taxed on their UK assets. So if he had a lot of assets, that would be quite important.”

Goodchild reiterated this point, noting that foreign residents frequently claim foreign domicile for tax purposes, and in such cases, the same would apply to succession law.