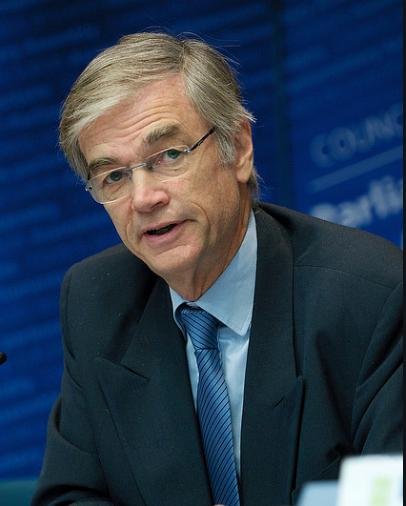

Will the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) start rendering its services for money? What are the reasons behind the court’s overload and the ways to deal with it? What difficulties does the ECHR face when interacting with national courts? ECHR Registrar, Erik Fribergh, spoke about these questions in an exclusive interview with the Russian Legal Information Agency (RAPSI).

- Mr. Fribergh, it’s better to start with the most essential: from your point of view, the European human rights system still remains well balanced and is able to withstand all the challenges in the context of the ECHR functioning?

- One thing that the Brighton Conference clearly recognized is that the main problem with the system set up by the European Convention on Human Rights lies in the Contracting States and not in Strasbourg. In other words it is the failure to implement effectively the Convention guarantees at national level – and particularly after the Court has already identified the problem – which is largely responsible for the Court’s excessive case-load. But we know that is not something that can be solved overnight and the Court has done what it can to adapt its working methods and procedures so as to enable it to deal more efficiently with different categories of cases. In this it has been greatly helped by the entry into force of Protocol No. 14 and especially by the introduction of the Single Judge procedure for inadmissible cases. Ultimately what is important is that the Court should be able to deal with the most serious allegations of human rights abuses rapidly and I think we can now say that we are in a position to work towards that goal, even if there is no room for complacency. In any event this does not dispense national authorities from taking the necessary measures to improve domestic implementation.

- The ECHR gradually enhances its approach to the European Convention on Human Rights, judges tend to apply a broader view on the Convention as a living instrument. National courts declare it to be an intrusion and it results in a conflict of interests, so to say, and mutual misunderstanding. What’s the solution of the problem?

- Well, let me say first of all that there is clear legal basis for the living instrument approach in the preamble of the Convention read in the light of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.

But even without this legal basis, it is plain that in practice the maintenance of human rights and fundamental rights requires the Court to ensure that the protected rights and freedoms continue to be effective in changing circumstances. This means taking into account developments in the law, in society and in science and technology. It hardly needs to be said that many aspects of contemporary human activity which by any definition fall within the intended sphere of protection of the Convention could certainly not have been envisaged by the drafters in 1950. To adopt a purely “originalist” stance would be to deprive the Convention of much of its relevance today. One only has to compare what is understood by family and private life in modern society with how they would have perceived in 1950 to see the difficulty of this approach. To restrict the content of the substantive rights to what one might speculate to have been the views of the drafters in 1950 would mean that aspects of family life which have since been recognised by national law would fall outside the protection of the Convention. The same is demonstrably true of for example developments in the fields of bioethics and communication. However visionary the drafters were, they cannot have foreseen in vitro fertilisation and the internet.

This does not of course mean that there are no limits to the interpretative evolution of the Convention. The Court recognises, and has repeatedly stressed, the importance of legal certainty, foreseeability and equality before the law and for this reason only departs from settled case-law where there are compelling grounds for doing so. Moreover the Court cannot by means of evolutive interpretation derive from the Convention a right that was not included in it at the outset. It cannot create new rights as opposed to applying existing rights in a changed context.

Another important self-imposed constraint is the use of the notion of European consensus to regulate the pace of Convention development. Where there is a sufficient degree of convergence in domestic laws of the States Parties an evolutive interpretation may be justified.

So I would say that the Court has a responsibility to ensure that the Conventions rights and freedoms remain relevant; to do this it has to keep pace with changes and where it does this on the basis of European consensus it will not often run into difficulties with national courts, although some disagreement is inevitable.

- On the whole, how the ECHR is going to further interact with the national courts of the European Council member states? It becomes obvious that proper solutions are needed as dialog and casual consultations are far from a success.

- Well, I believe, and this goes back also to the previous question, that national courts have a critical role to play in the Convention system and I therefore fully support initiatives to establish more dialogue and interaction between national courts, whether informal or formal. As you know the Brighton declaration calls for the introduction of an optional advisory opinion procedure, which would enable courts in those States which accept the procedure to seek advisory opinions on Convention issues. At the Court we are putting in place additional programmes for training judges from certain countries, financed by the Human Rights Trust fund. Another important part of this continuing dialogue takes the form of the Court’s judgments and this means making them available in a language that can be understood by national judges. This is why we have asked for and obtained from the Human Rights Trust Fund financing for an increased number of translations. But I wouldn’t say that the informal working meetings we have today with superior national courts are unsuccessful; on the contrary they make it possible for both sides to air their views and help to dissipate misunderstandings.

- Perhaps, such circumstances indicate strengthening of the ECHR position as a unique international institution of human rights protection?

- I am convinced that the role of the European Court of Human Rights is more important today than it has ever been. Yet in these times of profound economic crisis an international mechanism such as the Court can appear vulnerable to rather shortsighted and populist calls for a more nationalist approach to such issues as people tend to look inwards and backwards rather than outwards and forwards. International rule of law based on the protection of fundamental rights is the firmest basis for good governance and stability essential for economic recovery. I would not say that the Court needs to be strengthened, but it does need to be protected against any efforts to undermine it and weaken its jurisdiction. What might need to be strengthened, on the other hand, is the power of the Committee Ministers of the Council of Europe to supervise compliance with the Court’s judgments.

- Does the ECHR feel to be independent nowadays and how does the European Convention guarantee independence of the court? Even Mr. Bratza stressed this key issue in his speech in Brighton.

- It is true that in Brighton the President did stress the importance of guaranteeing the independence of the Court: judicial independence is as he said essential for a system governed by the rule of law. I think the Court does feel independent, but we consider that some of the language used in the Brighton declaration was unfortunate. It is I think misconceived to suggest that Governments, who are also parties before the Court, can dictate to the Court how the Convention is to be interpreted or how its case-law should evolve.

- By the way, what’s going to change for the ECHR after Brighton Declaration adoption? It will result in a new reform or it’s just an “extension” of the agreements met earlier in Interlaken and Izmir?

- There are different levels at which this question can be answered. Firstly, the Conference was expressly placed in the context of the follow-up to Interlaken and Izmir. It is not therefore a surprise that a lot space in the declaration is given over to endorsing or building upon what was agreed in the first two conferences. I think then that the main impact will be the continuation of that reform process. From the Court’s perspective for the third time in just over two years forty seven States have come together to reaffirm their commitment to the Convention system and their attachment to the right of individual petition and that is something extraordinarily positive, the fact that despite all the economic and political difficulties facing Council of Europe member States, there is a still a fundamental belief in the unique collective project which the Convention represents. As was said at the conference, trying to get 47 States to agree on anything is extremely complex so even if the result is not radical and perhaps in some places lacking in clarity, it does amount to a significant achievement.

- There are some critics, notably in the UK, who doubt that the goals set before the Brighton conference would be achieved as the Declaration is rather weak. What do you think about it?

- Well, I go back to what I have just said. I think the important thing is that we keep the Convention system in a state in which it can continue to be effective in achieving its goals and this means a more or less continuous process of adaptation in the light of evolving circumstances. We at the Court are trying to do this – we expect to be able to count on the support of Governments in line with their reaffirmed commitment.

- The amount of applications filed with the court and a number of pending cases still remains high and appears to be a hot topic. A filtering mechanism has been applied within the ECHR among other measures. Can you notice any positive changes?

- There has been a dramatic increase in the number of inadmissible cases decided as a result of the Single Judge procedure introduced by Protocol No. 14 and new working methods adopted to accompany it, in particular the setting up in the Registry of a dedicated Filtering Secretariat dealing with five of the States with the highest number of inadmissible cases. The latest figures indicate an increase of approximately 120%. For the first time since 1998 we are making some inroads into the backlog and with relatively modest recruitment of additional staff we believe that we can bring the backlog of inadmissible cases under control by 2015.

- The ECHR is going to charge applicants with the fee. When it’s going to be realized and, perhaps, you have already calculated the fee? Is it going to be refunded by the defendant along with the legal costs? Could you please share your ideas about how it might be arranged?

- This was a proposal made at an earlier stage in the reform process to which the Court has always been opposed. As far as I am aware there is not sufficient support for it among the Contracting States and it now seems unlikely that it will be taken forward. In any case there was no reference to it in the Brighton declaration.

- Mr. Fribergh, taking into account the trends we are talking about, are you sure the ECHR won’t end up with the customary bureaucracy?

- Well, of course the larger the institution the higher the risk of bureaucratic inertia. My challenge as Registrar is to ensure that the Registry remains a dynamic and motivated workforce at the service of the Court – that we are open to new methods and that we are ready to adapt to changing situations. I am convinced that most people who work in the Registry have a real sense of purpose and of the importance and value of what they are doing. I always say that it is a privilege to work for the Court and I hope this feeling is shared by the majority of my colleagues. We are conscious that the Court remains a source of hope for many victims of human rights abuses and we have an absolute duty to ensure that those complaints are processed and adjudicated in a reasonable time. Today everything is not perfect – it takes far to long to deal with cases from certain countries, but we are making progress and I am determined that this will continue for as long as necessary.

- Mr. Fribergh, thank you for your time.